Like most schoolkids in the US, I read the Diary of Anne Frank and learned how a young Jewish girl and her family lived in hiding for two years from the Nazis before they were found and sent to German concentration campus. Anne died in one of those camps at the age of 15 in 1945. She left behind a compelling story about the human experience, told by a thoughtful and optimistic young girl, that doesn’t even hint at the true horrors of the Holocaust — her diary ends before she was sent to the infamous Bergen-Belsen death camp.

But did you know that Frank’s father, Otto Frank, knew war was coming and that it wasn’t safe for his Jewish family? Or that he had applied for visas to the US – he had money and connections in the Roosevelt administration – but was denied entry to America before he and his family went into hiding?

I didn’t know that, and that’s part of the goal of a new six-and-half-hour documentary directed and produced by Ken Burns and his partners Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein. Called The US and The Holocaust, it offers a deep dive into what they describe as “America’s response to one of the greatest humanitarian crises in history.” The three-part series, narrated by Peter Coyote and including the voices of Liam Neeson, Paul Giamatti, Meryl Streep and Werner Herzog, is available to stream on PBS.org.

The filmmakers combine first-person accounts from Holocaust witness and survivors, commentary by historians, source documents and archival photos and video footage to dispel “myths” that Americans were either ignorant of or indifferent to what was happening in Germany before and during World War II, Burns and Novick said in an interview.

Our conversation took place days after immigrants and asylum seekers in the US made headlines after reportedly being transported under false pretenses by a Republican governor as part of a plan to move immigrants out of certain states. Both Burns and Novick say today’s immigration challenges underscore that the issues around racism and antisemitism that America was grappling with in the 1930s and 1940s remain unresolved – which is why the series includes footage of the white-supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, where some shouted “Jews will not replace us.”

While they could easily have focused on heroes and villains, Burns and Novick said their aim is to provide a fact-based, historical account of how the US handled this crisis and to let the words and actions of US policymakers, journalists, religious leaders and other influencers speak for themselves as to how governments and people responded to Germany’s persecution of its Jewish citizens. It’s a fact that the US accepted more World War II refugees than any other nation at the time, Burns and Novick note. But it’s also a fact, they add, that America could have done more to help millions of people who were trying to escape persecution by the Nazis.

“It’s really the story of the US and the Holocaust – what we knew, when we knew it, what we did, what we didn’t do – perhaps, what we should have done,” Burns said. “It is important to us … that we are disciplined so that we’re not sort of pointing arrows and neon signs at those things, but just say … human nature doesn’t change. There are many things you could point out about our Civil War series or the Vietnam series or Prohibition that rhyme, like Mark Twain might say, with the present.

“Our job is not really to, in any way, to parse them or suggest that we had ulterior motives,” he added. “We’re umpires calling balls and strikes.”

Novick said the documentary also seeks to address the question of what “America,” a nation founded by immigrants, is all about. “It really is a film about America’s sense of ourselves, who we are as a nation. Are we a nation of immigrants or not? What does the Statue of Liberty really represent, and how much do we live up to that?” she said. “So it’s about more than the Holocaust – not to say that the Holocaust isn’t a worthy topic, which it is. But it’s really about our relationship to this event.”

In addition to the series, the filmmakers worked with the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, PBS Learning Media and Holocaust experts to provide educational materials for middle and high school students. That material is available at the Ken Burns in the Classroom site.

I spoke with Burns and Novick about the Holocaust, their seven-year investment in the series and their approach to storytelling. Here’s an edited version of our conversation.

On the surface, this is a documentary about the Holocaust and America’s response to it. I can’t help but note we’re talking about how America views immigration then versus today just a few days after some US governors bused or flew immigrants from their states to other states. Could you describe what this series is about and if there’s a deeper purpose to the story you were trying to tell?

Burns: I don’t think it has a deeper purpose. It’s really the story of the US and the Holocaust – what we knew, when we knew it, what we did, what we didn’t do – perhaps, what we should have done.

We have, in almost every film we’ve made, realized that those films have resonated in the present with issues or events. But it is important to us for the kind of films that we wish to make that we are disciplined so that we’re not sort of pointing arrows and neon signs at those things, but just say, you know, human nature doesn’t change. So there are many things you could point out about our Civil War series or the Vietnam series or Prohibition that rhyme, like Mark Twain might say, with the present.

Our job is not really to, in any way, to parse them or suggest that we had ulterior motives. We really wanted to know what happened, and that’s what we were telling. We’re umpires calling balls and strikes – and that’s very, very important to us. So we can’t claim any alternate kind of meanings other than to say that we understand there’s an urgency right now with what’s going on.

The Hilsenrath family — from left, Joseph, Anni (holding unnamed child), Israel and Susi — who were fortunate to have escaped Hitler’s Germany. Susi would later be interviewed for The US and the Holocaust.

US Holocaust Museum

Novick: I completely agree. It’s not a story about the Holocaust pretending to be one thing and being about something else. When we talk about what the movie is about, it’s about America’s response to, not role in, the Holocaust. We didn’t have a role in the Holocaust.

In order to understand that question, we just [had] to understand, well, it was really hard for people to get here when they were desperate. Why? My ancestors just got on a boat and came over here. There were no rules. There were no restrictions for a long period of time until the Chinese Exclusion Act [of 1882]. So we realized that we have to ask ourselves the questions about how this happened – that our response was what it was to the refugee crisis and to the humanitarian crisis and the lack of a more muscular response to the rise of Hitler.

It really is a film about America’s sense of ourselves, who we are as a nation. Are we a nation of immigrants or not? What does the Statue of Liberty really represent and how much do we live up to that? So it’s about more than the Holocaust – not to say that the Holocaust isn’t a worthy topic, which it is. But it’s really about our relationship to this event.

One of the fascinating things we discovered is the interchange of ideas between the United States and Western Europe in particular, in the years leading up to Hitler coming to power that stoked our immigration backlash. You know, eugenics and racial science and dividing the world’s peoples into races, giving them different weight in terms of their significance and importance and capacity to be worth existing on this Earth. All of that is part of our history, too. So it’s really just trying to understand the context of what happened. We had to keep going back and back and back. And some of those threads really do pull through right to now.

You shared some things that even people who have studied the Holocaust and have written about it for a very long time didn’t know with regards to Anne Frank and her family.

Burns: What’s new, not our own scholarship but recent scholarship, is that Otto Frank, after he moved his family from Frankfurt to Amsterdam and [they] were living comfortably, understood the writing on the wall and was desperately seeking a way to get his family well out of harm’s way to the United States. He had the means, he was a successful businessman. He wouldn’t be a ward of the state. He had the contacts – contacts in the United States, [he] knew people in the Roosevelt administration.

He did everything he possibly could, and the United States did not let [in] the family of Anne Frank, which is perhaps for most Americans the only real story they know of the Holocaust. And certainly for many of our schoolchildren, the way they’re introduced to it is through this diary that actually doesn’t detail the Holocaust but details the rise of Nazism and having to hide from the Nazis because they’re a Jewish family in Amsterdam once Holland is overrun.

When we investigate something, we invariably outrun anything we ever knew ourselves. And, the scholarship provides us with an opportunity to just sort of humbly go to ourselves, “I didn’t know that.” And what’s always gratifying is that our audiences, our critics say, “I had no idea.”

As Lynn said, this really haunting question that animates all of our work is, who are we? What does it mean to be an American? And a lot of the questions in this is that people are saying that some people are real Americans and other people aren’t real Americans. Or that we should keep America for the real Americans and not let other people in, though we are a nation of immigrants.

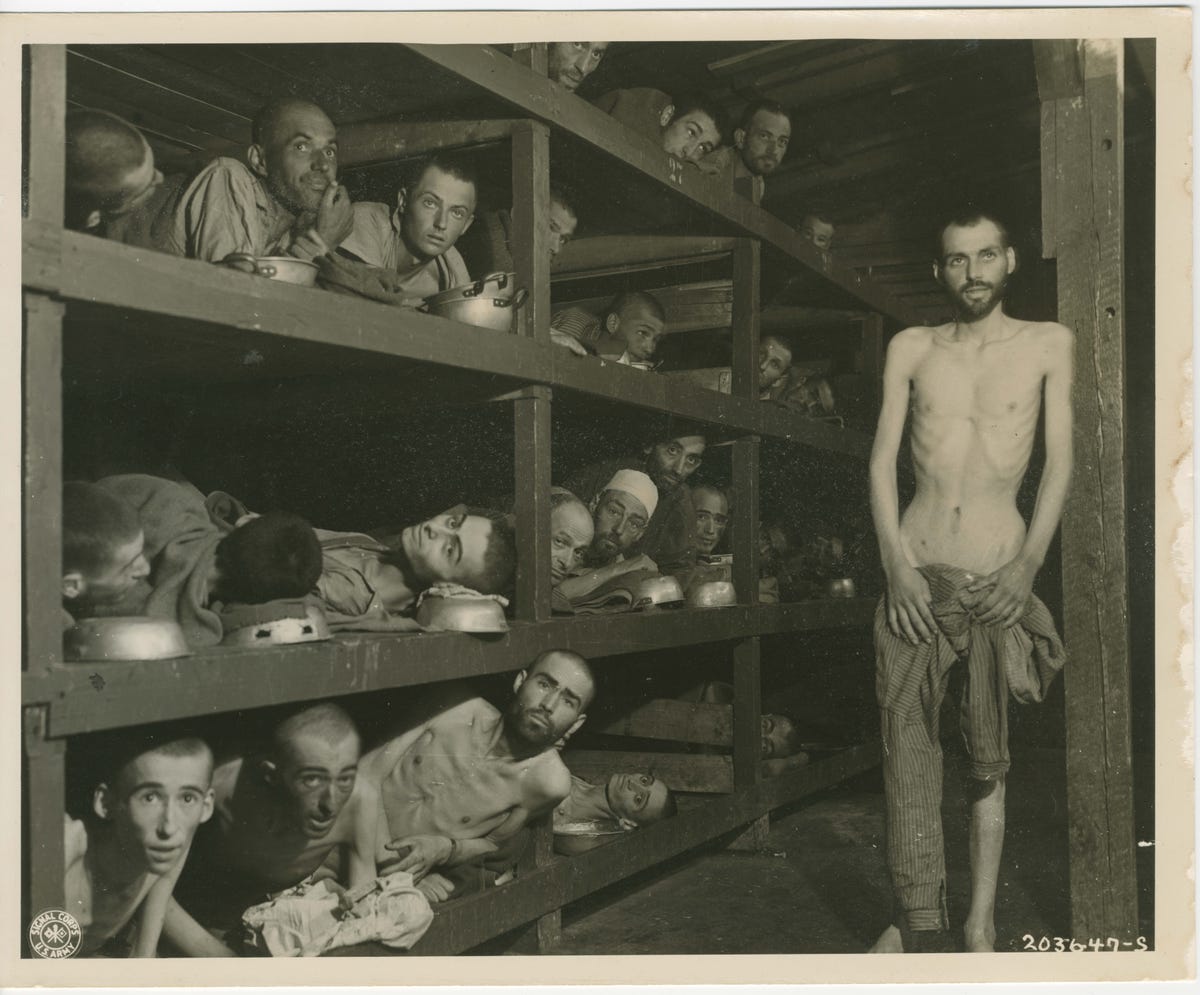

Former prisoners of Buchenwald concentration camp are pictured in the wooden bunks where they slept. Elie Wiesel, author of Night, is pictured in the second row of bunks, seventh from the left, next to the vertical beam.

National Archives and Records Administration

These are really complicated things, and they certainly mirror things that are going on today, stuff we’re talking about, worries that we have, anxieties that we have. For us, history becomes a place where you can have a slightly more dispassionate conversation, that you’re able to talk about it without the arguments over the Thanksgiving table about “you voted for him?”

This is our seven-year labor of love and of heartbreak that reveals what happened in the Holocaust, but also what the US relationship to it was. You have to stress again and again, the United States had nothing to do with the Holocaust.

But as Lynn also said, these ideas of racism, of antisemitism, of nativism, of anti-immigrant xenophobia are part of the stuff that’s going on here and going on in Europe. And so one of the reasons why the United States seems paralyzed at a point when they could have gotten out hundreds of thousands of more people – we did let in 225,000, more than any other sovereign nation – but we could have let in a million or 2 million and therefore relieved the strain. We didn’t do it. And it’s because of these ideas that are still prevalent and in the air today and part of the complicated story of not just the US, but humanity.

Novick: I remember when we first started talking about the idea of the film on the US in the Holocaust, in collaboration with the United States Holocaust Museum, back in 2015. Front of my mind was this question of who’s a real American. What do we do about immigration or about refugees? What do we do about atrocities overseas?

We’re having that conversation now, but we were still having it in 2015. It’s just a little bit different context because our sense of the dangers of authoritarianism seem to be: something that happened somewhere else. I don’t think I was prepared for the growing sense of madness that it could happen here.

In addition to the story of Anne Frank, I was most struck, based on your historical research, how much Americans did know about what was happening in Europe at the time. As you pointed out, Ken, most students only learn about the Holocaust in a few pages in a textbook with a photo of Anne Frank. Can you talk about that?

Burns: It was “We didn’t know about it.” “What a horrible horrible thing it was.” And so I think Americans have spent several decades in a plausible deniability about it, when in fact, the research bears out that even in 1933, the first year of Hitler’s regime, there were 3,000 stories in American newspapers about the mistreatment of Jews.

Everybody knew what was going on. Now, to be fair, there’s a Depression going on, and it is the greatest economic dislocation in the history of certainly the United States, but also the world. Hitler’s rise to power is in some ways fueled by the frustrations and the anxieties and the tensions exploited by his authoritarian inclinations. But people are worried about jobs and putting food on the plate and they inherited this eugenics thing. They’ve now got an immigration law that’s based on eugenics – basically, those Nordic countries that are Protestant and white have better people…

We also have rampant antisemitism in the United States from almost every quarter. People like Henry Ford telling us this daily, and radio priest Father Coughlin spewing antisemitic rants to millions of people on his radio show.

And so you have people that are not disposed to take the information and know what to do with it. It’s also an isolationist country that feels that they were lied to about the First World War, that there had been a lot of exaggerated anti-German propaganda. Remember, lots of Americans are of German descent. So you’ve got this horrible brew, a toxic mixture of things that then doesn’t jibe with the immigration law. It hamstrings the politicians who might want to change things and do try to change things. And then you’ve got institutions like the State Department that have, periodically, an antisemite here and an antisemite there.

I think it’s easier to say we didn’t know. One of the startling facts that our colleague, Sarah Botstein, a co-director with Lynn and me of this film, says is that of the polling [of the time] that we cite throughout the film, the most stunning one is towards the end. That after all the films are released, all the concentration camps are liberated, the war is over, Hitler is dead, there’s no more killing of Jews – there is a continued profound refugee crisis of displaced persons in Europe, many of them Jews.

The United States does not want to let in anybody either. The polling is like 5% of Americans want to let in more people, even after you’ve looked at the most gruesome footage from the liberation of the concentration camps. I think it’s safer for people to spend those decades like an ostrich with their head in the ground with those two pages, [the] picture of Anne Frank, whose diary covers not the Holocaust, but the leadup to it.

This is what we have to reckon with. We have to reckon with this part of ourselves, just as we are more than happy to reckon with the positive things that we’ve done. I mean, we won that war, our manufacturing, Soviet sacrifice and our own military sacrifice of hundreds of thousands of Americans for the cause, not of the liberation of Jewish people, but for the liberation of Europe, the idea of freedom for what the Statue of Liberty originally stood for, which was that democratic government is the best way to go. Right? Period, full stop.

We had mostly open borders from 1870 to 1920, and that provoked the backlash. But let’s remember that millions upon millions of people fled economic uncertainty and persecution and totalitarian governments – and pogroms in the case of many Jews – and found sanctuary and have contributed immeasurably to who we are. And so this becomes a tragic moment when we had an opportunity to let in a lot more people than we did.

Novick: I think those of us whose ancestors came in that great wave can see that there’s an energy and there’s a dynamism and there’s a creativity and there’s a power that comes from diversity and inclusion, pluralism, that these waves of people brought to our nation were for the better. But everybody didn’t feel that way at the time, especially the people who, as Ken says in the film, they were afraid of being replaced, outbred, outnumbered. They could see their hegemony, their power, slipping through their fingers because they were going to be in the minority.

In today’s fast-paced, social media-first world, will people take the time to watch a six-and-a-half-hour documentary? Will the people who need to see it watch this?

Burns: You have the opportunity, you hope, to change minds, or to at least permit the possibility of a good story to get inside you and make you think and kind of rearrange your molecules, if you know what I mean, and do that.

I am not so worried about it not reaching the right people. The people who cannot be reached cannot be reached. But there are a lot of people who are curious about history, curious about the way we tell stories. The reactions that you had will be different from the reactions of your neighbor, even a relative. And so we’re just happy to let the story go. We’ve worked really hard on it, and now it’s yours. It’s not really ours.